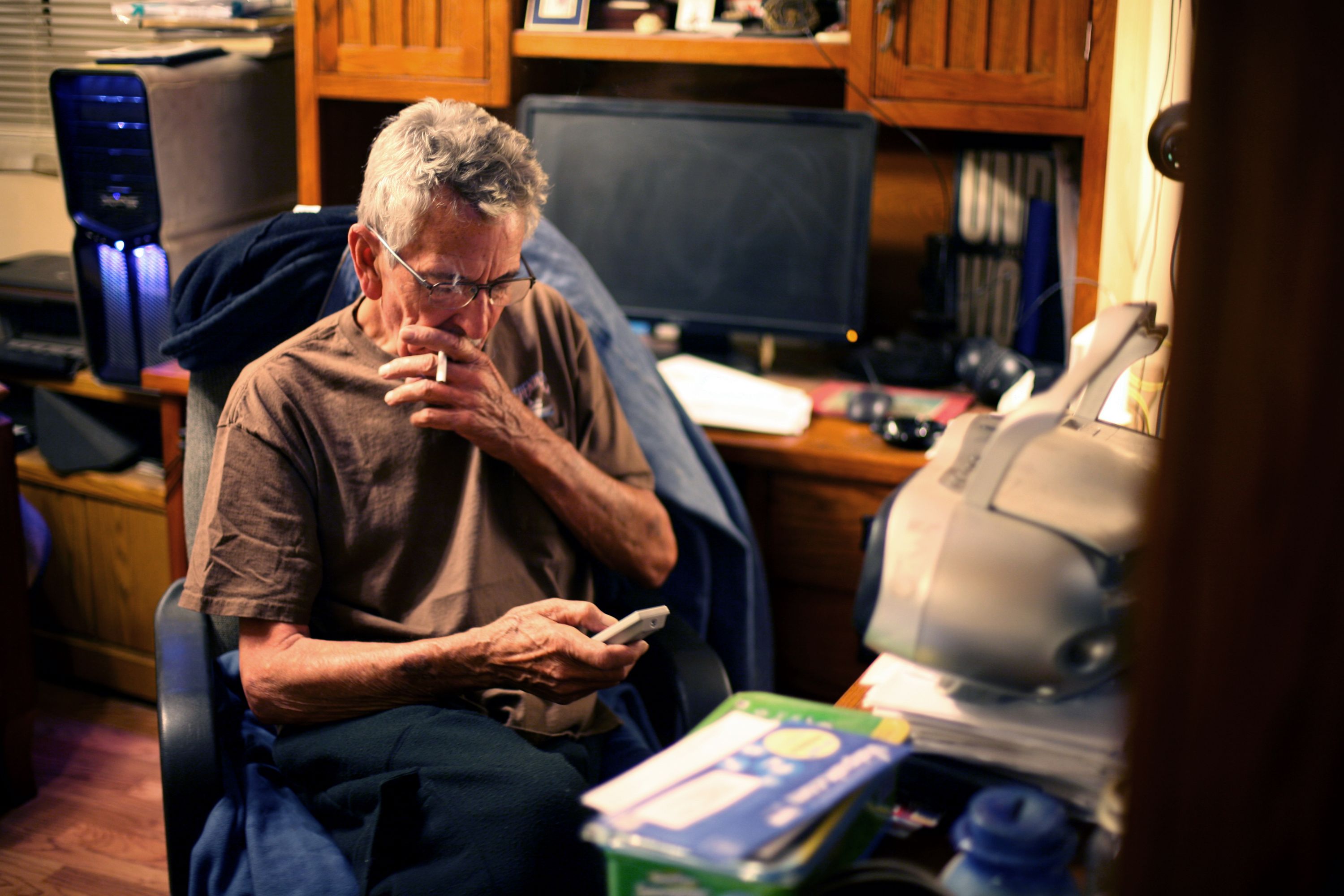

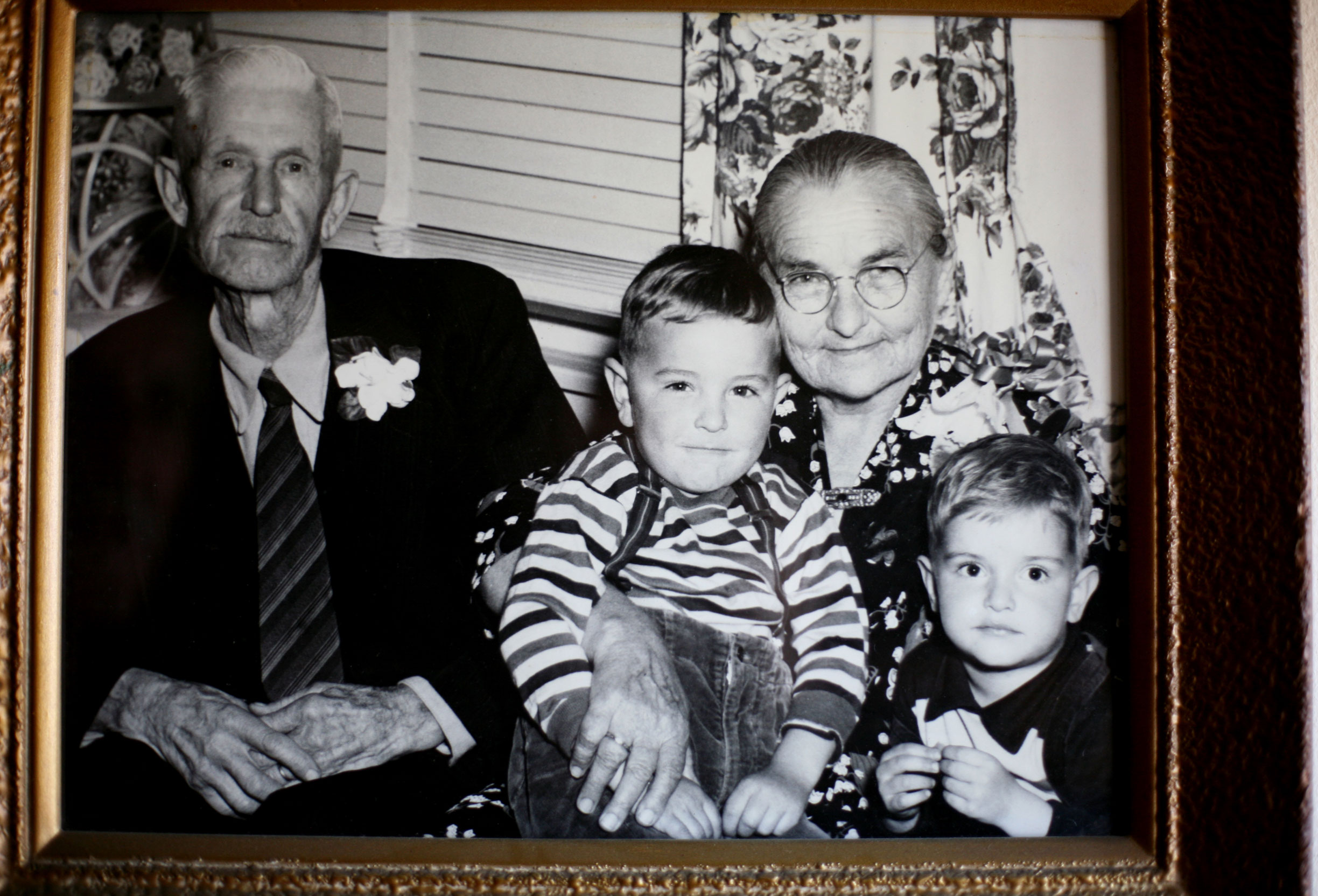

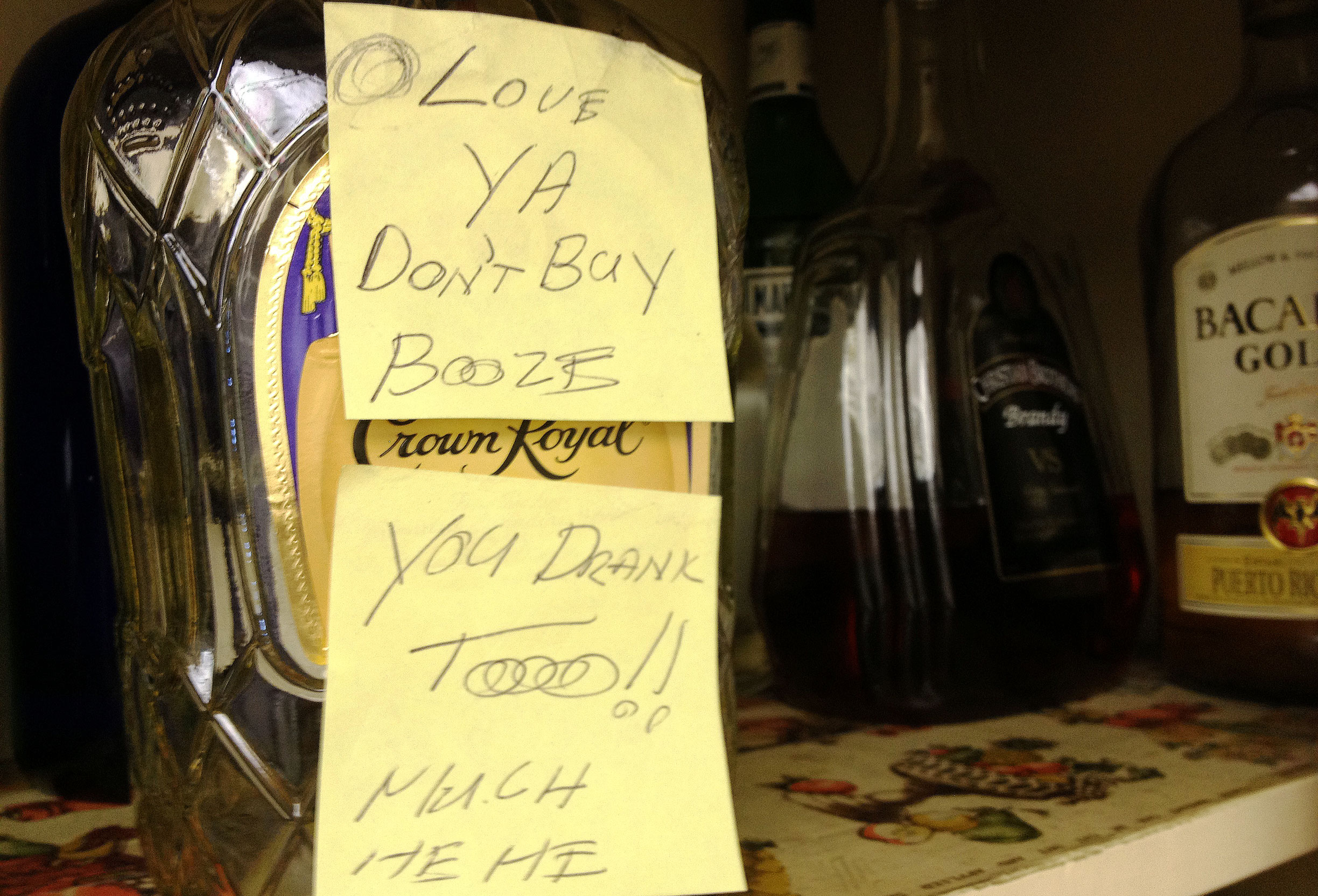

Early morning sunlight streams through the blinds as John Ostoich pours his first bourbon of the day. A cigarette hangs from his lips; his parrot, Bok-Bok, rests on his shoulder. Johnny O, as he’s known, has spent most of his 68 years working on the San Pedro waterfront. His skin is leathery and creased after decades of working on the docks, but he still has a twinkle in his eye. “The ocean is my mistress,” he says. “She is beautiful and dangerous.”

Johnny O tends to his parrot, Bok-Bok. “She’s already been on my shoulder this morning and had tobacco and coffee,” he says.

For decades Johnny O worked as a linesman, literally using rope (also called line) to secure the ships to the docks. It’s one of the oldest and most dangerous jobs at the port. Depending on the size of the ship, the rope can be over a foot in diameter and take up to three men to handle. “This will take your legs off,” Johnny O says about a one such rope called the anaconda.

“I’ve seen a crewmember get his head chopped off laying on the top of a deck of a ship,” says Johnny O.

Johnny O has seen a lot of change at the San Pedro waterfront and has had to adapt. Before working as a linesman, he was a commercial fisherman. When that industry moved overseas, he became a master mechanic in the longshore union. Finally, he settled in at the Lines Bureau as a dispatcher, a so-called “antique” in charge of the linesmen who report for work on the docks day and night. He says it’s an easy job reserved for men too old to be hauling lines. But antique? He prefers to think of himself as a pirate.

Reporter’s Notebook: Life on the Waterfront

Linesmen are the men and women who tie ships to the docks with lines. It’s a pretty simple job; so efficient in its old-fashioned-ness that machines can’t do it any better. And around here, where container terminals are automating and longshoremen fear for their jobs, that’s something.

When I meet Johnny O, he works at the National Lines Bureau, one of the companies that dispatch linesmen.

On a December morning, he brings me into his inner sanctum at “the boys’ house,” a bungalow he shares with his two sons. He’s irritated that I’ve come so late – 7:30 a.m. He won’t let me turn on my tape recorder until he “understands the format of my show,” but really, he just wants to check me out. He wants to know if he can trust me with his secrets. We have a bourbon or two, maybe three. Smoky, golden light streams through the blinds. Johnny O places Bok-Bok, a small orange and yellow parrot on his shoulder and he reveals that he’s a pirate. Meeting a pirate is an irresistible way to start a project. And this pirate seems to encapsulate many of the changes that have taken place on the waterfront. Johnny O started out on fishing boats until the fishing industry in San Pedro dried up. He’s fixed boats and ships and cars and planes. He became a mechanic in the longshore union and finally a dispatcher at the Lines Bureau.

Eventually, I ride into the harbor on a foggy night to see Mark Coynes and Rob Lukowski board the biggest ship to call the Port of Long Beach. I visit a run down taco-stand of a building to see casual workers, the workers at the bottom of the totem pole, struggle to pick-up jobs shift by shift. I meet former union leaders Peter Peyton and James Spinosa Sr. – known to all by his nickname Spinner – who have tried to prepare and protect their union brothers and sisters from automation. On a day when no one will agree to an interview, I meet Harold Ericsson who tells me about a miracle he experienced at the steel dock over 30 years ago.

Somehow all of this leads me to a dusty construction site: Middle Harbor, a 9-year $1.3 billion project to develop an automated terminal at the Port of Long Beach. It’s estimated that this one terminal could eliminate 50 percent of the jobs here. Rich Dines, one of the commissioners, takes me on site. Cranes loom like dinosaurs at the water’s edge. He pulls out his phone to take pictures of them. “These are the largest cranes ever manufactured.” He explains that there will be a handful of workers on raised platforms, but that the rest of the container yard, usually full of longshoremen buzzing around in vehicles, will be free of people.

- The tallest cranes in the world can be found at Middle Harbor, which is expected to fully upgrade two existing container terminals by 2019.

- Rich Dines, Harbor Commission Vice President stands in front of an automated vehicle, which operates without a driver.

- Port of Long Beach Executive Director J. Christopher Lytle calls Middle Harbor their flagship model for ‘The Port of the Future.’

They say these kinds of terminals are unusually quiet. So quiet, they’ve earned a nickname: ghost ports. Standing there, I try to imagine this ghost port. The gentle whir of machines… the lap of water against the docks… the squeal of seagulls… the occasional bang of a container touching down… the voices of the linesmen as they haul the lines.

— Cargoland Producer, Lu Olkowski